The Federal Government of Nigeria has taken a not-well-received step with the signing of the Insurance Industry Reform Act 2025, mandating insurance for public and multi-unit buildings.

While the policy seeks to bolster safety and liability protection, it also risks adding pressure to an already fragile housing market potentially raising rental costs for tenants least able to afford them.

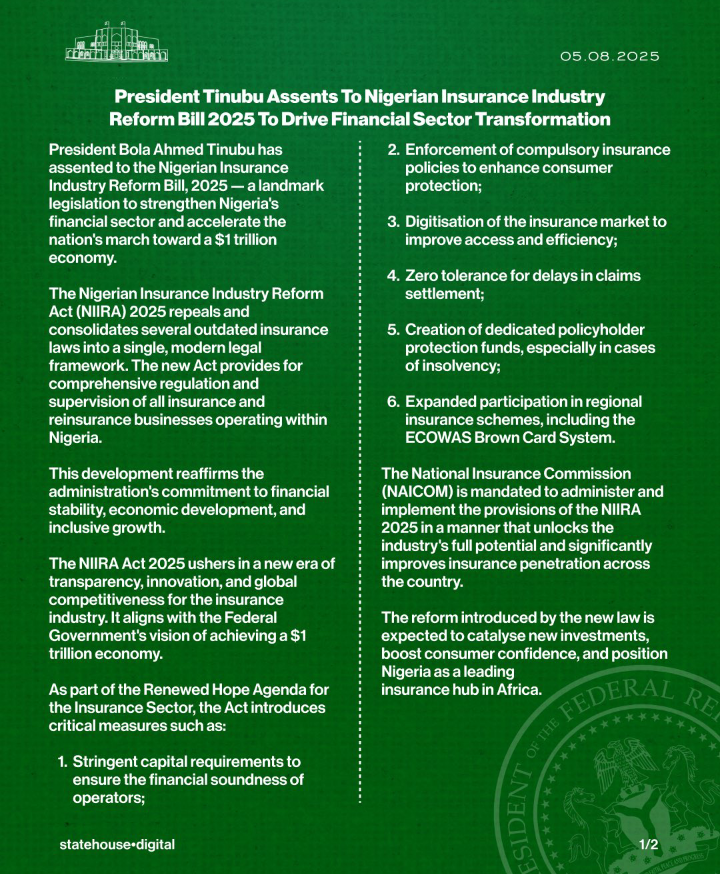

The New Law

Under Section 76 of the Act, public buildings, defined to include tenements, hostels, offices, schools, and other buildings accessible to the public must now be insured against perils like fire, collapse, floods, earthquakes, and storms.

Landlords face steep penalties for non-compliance: fines of at least ₦1 million, up to 12 months in jail, or both, with NAICOM authorized to seal buildings deemed unsafe and uninsured.

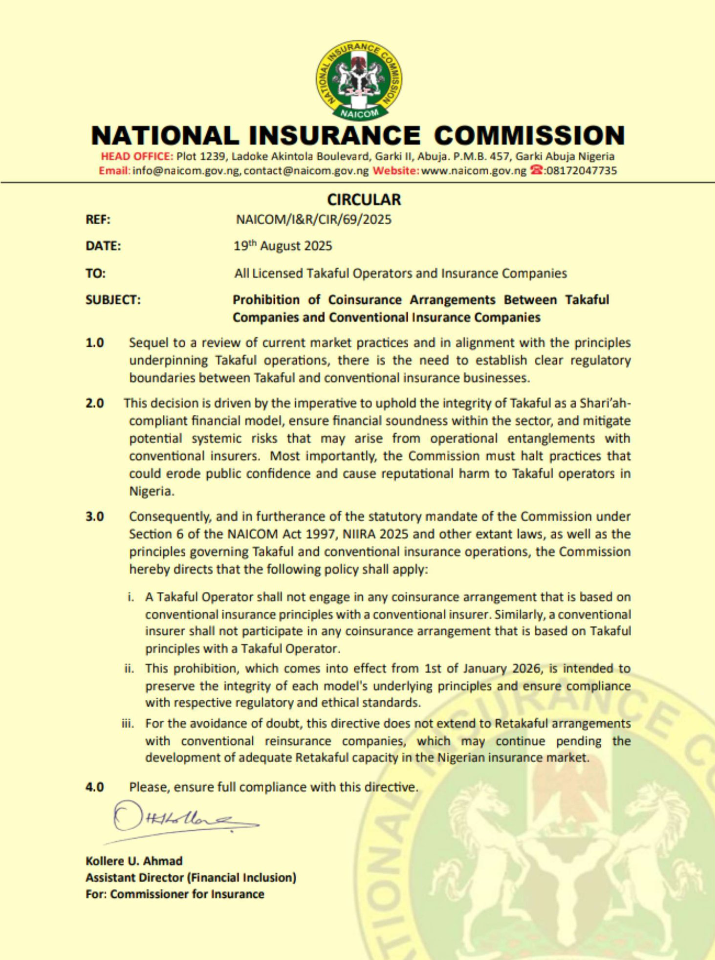

The National Insurance Commission (NAICOM) communicated the nitty-gritty of this law in a post on their official X page.

The law also imposes insurance obligations on:

Federal government assets and employees (Section 77)

Petroleum and gas stations, including coverage for vehicles transporting fuel, violators risk at least ₦1 million fine or two years’ imprisonment

Additionally, insurers themselves face stricter penalty, including penalties up to 10 times the payable amount or license cancellation for persistent defaults in claim payments

Why It Matters

Previously, although elements of compulsory building insurance existed in older laws like the 2003 Insurance Act, enforcement was weak and compliance rare.

This reform represents a leap forward in regulation and public safety.

By making insurance a legal requirement, the reform aims to protect tenants, occupants, and the general public from the devastating aftermath of structural disasters or accidents.

A Hidden Cost for Tenants?

Despite its protective intent, Nigerians warn of unintended consequences, namely, increased rental costs.

In a rental market already strained by inflation, supply shortages, and high maintenance costs, this additional compliance cost for landlords may be passed down to tenants.

As one property sector expert explained, landlords “adjust rents in line with replacement costs”, factoring in utilities, security, and other services not reliably provided by government adding insurance premiums to that mix could further drive up prices

This comes at a time when affordability is already a challenge.

Many Nigerians pay rent annually in advance, a burden exacerbated when incomes are suppressed by economic instability.

The added cost of insurance may push low-income renters further to the margins, into suburban or peri-urban areas with poor transport access, as they juggle limited budgets.

The policy’s success hinges on transparency and enforcement. Landlords must visibly display insurance certificates, particularly at fuel stations or among public buildings.

NAICOM’s authority to seal non-compliant structures signals that the government is serious but many tenants may not understand how these new rules apply or how to hold non-compliant landlords accountable.

Conclusion

Nigeria’s Insurance Industry Reform Act is a commendable step toward safeguarding public welfare and mitigating disaster risks.

But without careful implementation and support, it risks becoming another indirect tax on housing, one that low-income residents cannot bear.

Insurance should be a shield, not a burden. Nigeria’s housing system must exist to protect people, not push them out of safe homes.

Watch a video of a concerned citizen on X.